What’s the best way to generate business with large Asian companies?

If you’re expecting an easy answer, I will have to disappoint you. But gaining a thorough understanding of the way these corporations work is an absolute must.

If you’ve ever tried to list your potential customers in Asia, there’s always a plethora of companies with Sumitomo, Samsung and the like attached to their names.

“Samsung is Samsung – so if I’m talking to someone with its logo on their business card, surely I’m making progress?”, you might say. But there are important implications for how you need to conduct business stemming from the way these vast organizations are structured.

I gave a talk about this a few months back for our APAC workshop series and now, following several requests, here’s a deeper dive into the topic …

Corporate cultures

Let’s start by looking at Asian business cultures.

It’s well known that these are vastly different from their western equivalents. Asian companies, for example, tend to emphasize the importance of the group over the individual, and this is reflected in team, department, company and ultimately group formations.

This ‘team spirit’ permeates everything companies do and its benefits include tighter collaboration with partners, loyalty to stakeholders and a comprehensive approach to issues.

But it can also have adverse effects including ambiguity of roles and responsibilities. Amongst Japanese corporations, in particular, it can lead to extremely lengthy decision-making processes.

These factors can frustrate market entry hopefuls unused to a level of corporate bureaucracy characterised by many meetings with different teams and endless requests for additional information. But the well-intentioned goal – roundabout as it may seem – is to make sure all bases are covered before putting ink on paper.

To mitigate some of the frustration, try putting yourself in the shoes of your Asian counterparts. And understand exactly how each organisation works on the deepest level.

Formation of the Japanese giants: the zaibatsu

Have you heard of the ‘Big Four’? We’re not talking accounting firms here ... Sumitomo, Mitsui, Mitsubishi and Yasuda were the original Big Four Japanese family-run businesses that later went on to expand into vertically integrated conglomerates.

In Japanese, these were historically referred to as ‘zaibatsu’ - and they go way back: Sumitomo has its roots in the 1600s, and the other three rose to prominence in the 1800s. Each had different starting points, ranging from minerals to logistics, and all contributed greatly to Japan’s ability to catch up with the west during the first industrial revolution.

The formalization of the zaibatsu took place around Japan’s rapid industrialization in the Meiji Period (1868 – 1912) and saw these family holding companies establish a myriad of subsidiaries spanning different industries, all served by each zaibatsu’s own bank providing cheap cash for investment and expansion.

This created a tight network of companies that operated under one umbrella to serve different sectors. How the zaibatsu grew to the size they were, and the political power they wielded during the World Wars, is a fascinating piece of history, but best left for a separate article. Suffice to say: they played their cards very well.

Re-organizing for the modern economy: the keiretsu

The zaibatsu’s industrial and economic dominance couldn’t last forever as we entered modernity. After the Second World War, several societal changes took place in Japan. One of these was the dissolution of the zaibatsu structures to curtail monopolization and make the market more competitive.

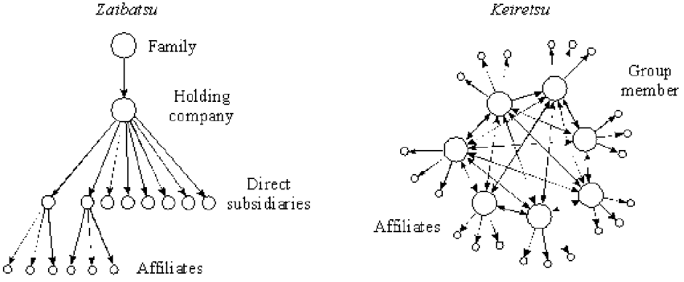

In response to this, zaibatsu were reformed into ‘keiretsu’. A keiretsu is either a horizontal or vertical group of companies interconnected through cross-shareholding rather than a direct ownership chain linking back to one family (see below).

Comparison of zaibatsu and keiretsu structures

Source: Yonekura

Information sharing, collaboration and joint investment between keiretsu companies yield a stronger group overall – and imbue it with a sense of a true team effort. This is especially evident in the more vertically structured keiretsu companies like the Toyota Group, where ‘lower rung’ subsidiaries, through their technological prowess, add value to the top company’s end products.

In modern Japan, while many group companies operate as independent entities, there is still a good deal of information sharing and task division that takes place across the mesh-like structure.

Why reinvent the wheel? South Korea’s chaebol

On the other side of the Korea Strait, the influence of Japan’s zaibatsu can be seen in the way Korean conglomerates developed structures that are today known as ‘chaebol’.

Just as in the case of zaibatsu, their history can be often traced back centuries, but chaebol as we know them today took off in the 1960s as South Korea’s industrialization experienced a post-Korean War boost.

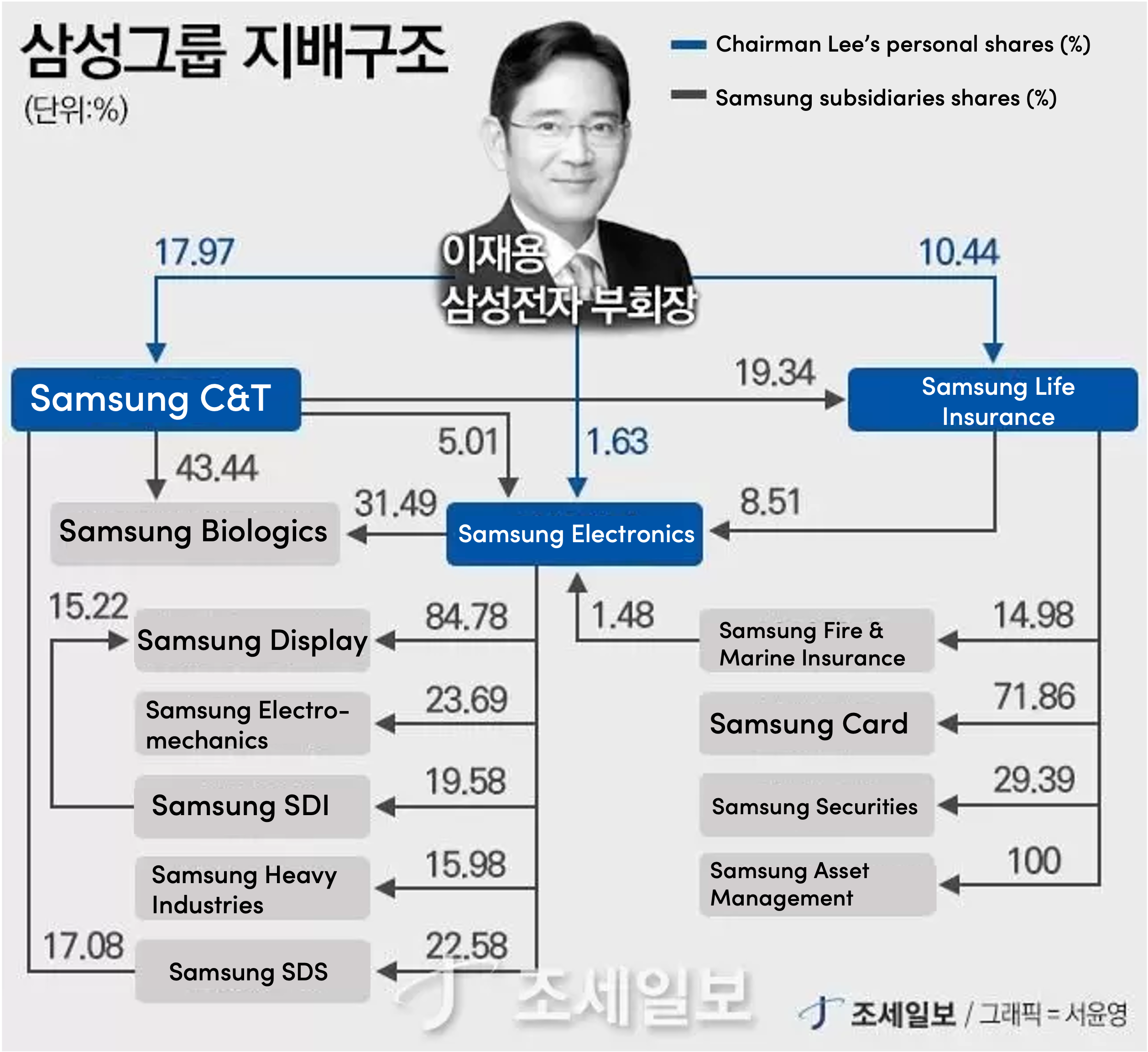

Family-controlled conglomerates such as Samsung and Hyundai are examples of globally known chaebol, which are similar in structure to Japan’s zaibatsu but with cross-shareholding aspects typical of keiretsu. Chaebol are centred around a family dynasty with many of the head family members holding senior management positions (see below).

Samsung structure

Source: Joseilbo

In fact, chaebol cross-shareholding schemes are often so sophisticated that, even with relatively small stakes in each group company (mandated by law), the head family retains near-total control of the whole group’s operations.

One key difference from zaibatsu is chaebol are not backed by their own financial institutions: there have traditionally been legal limitations on the financial services they can provide within their own companies.

This was a way for the government to ensure it maintained policy control over the distribution of capital and could channel funds to favoured projects during the country’s rapid development phase. When a company proved successful in a nationally-sponsored venture, the government would often reward it with further funds for new initiatives. This encouraged horizontal structures to develop within the chaebol as successful firms in one field were encouraged to move into others.

So, while chaebol didn’t have zaibatsu’s flexibility to move their own capital whichever way they pleased through group-owned banks, they did receive considerable government support.

Why does any of this matter?

Now that we have a basic understanding of the background of the Japanese and Korean behemoths, how can we use that to our advantage?

For starters, when trying to do business with keiretsu or chaebol, it is crucial to understand both the structure and the culture within each group.

While Toyota, for instance, is the primary target for many international automotive technology providers, the path to having your solution implemented in an end product – like a shiny new car – likely won’t be directly through the OEM. Instead, you should focus your efforts a step down Toyota’s vertical group ladder to engage tier-1s like Denso and Aisin.

Or perhaps you’d be wise to step even further down and target cutting-edge R&D organizations, like Mirise Technologies, which supply the tier-1s. It is often at this level that you’re best to initiate talks with a specific system, sub-system or component engineering team conducting research and proof-of-concept work that could benefit from your technology. These are the people who influence the ultimate decision-makers at OEM-level. And, to secure a deal, you’ll need them on board.

Imagine the reverse: you somehow wow the OEM product team lead – who, by the way, doesn’t always grasp all the technicalities and hurdles to making the product – so a memo goes to Mirise and Aisin engineers: “Make it happen!”. That’s good, right? They’ve got their orders...

But that violates the ethos of team spirit. The engineers might feel reluctant to prove your tech is as good as you say. And they might not be welcoming to your team who are trying to teach them how it works. This may well lead to a lose-lose-lose situation: the engineers won’t deliver, the product lead will embarrass themselves in front of their bosses, your reputation will be damaged and doors will close for you across the group.

Talking to the right group company from the beginning and building rapport with all stakeholders within the chain will fortify your position and create momentum as you progress towards discussions with the ultimate decision maker for the solution you’re bringing to the market.

In organisations like Toyota, decisions are made through group consensus, not by whims of individuals. Bottom up, not top down.

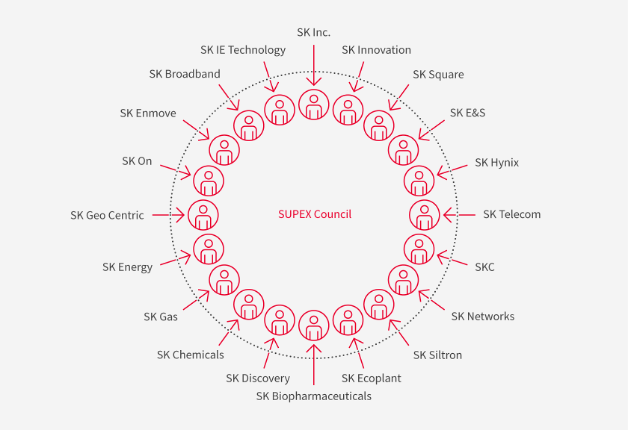

For Korean chaebol, the structure varies from one group to another. While some are tightly integrated, others have individual companies that operate independently. For instance, in the case of SK Supex, which is the SK Group ‘council’ representing the interests of all its major businesses (see below), you can often start at the top with high-level ideas and get introductions to the right teams within its subsidiaries.

SK Supex

Source: SK

But in cases where a group’s companies are independent, you’ll need to research and reach out directly to the right subsidiary. For example, you won’t be able to get into Samsung SDS (the group’s IT consulting arm) by approaching its parent company, Samsung Electronics. Instead, you’re better off approaching relevant departments at Samsung SDS directly.

In some cases, the lines between subsidiaries blur and it’s tricky to get a clear understanding of each. For example, LG Energy Solution deals with battery technologies, while LG Innotek – LG’s electronic components subsidiary - is also involved in batteries, but only for small applications.

To close deals with Korea’s chaebol, similarly to Japan, the process requires rigorous back and forth with technical and commercial teams to gain consensus, so knowing your best starting point and being patient are key.

Success stories

Sounds good in theory, but let’s look at concrete examples of western companies that have sold into large Asian conglomerates.

In the cybersecurity space, we had a US operational tech (OT) security client who wanted to enter the Japanese market and was looking for partners. Toshiba is one of the key players in the space and so was a prime target. But Toshiba Group is horizontally divided into different types of businesses with more than 100,000 employees globally.

So, whom should we approach to achieve our goal in an efficient and timely manner – and without disturbing Toshiba’s preferred decision-making process? At first glance, targeting Toshiba Corporation, the top company, might seem the obvious choice. That’s where the decisions are made, right?

Wrong. Toshiba has group companies focused on everything cyber and digital, as well as those that implement such solutions. Approaching these specific group companies and getting initial validation from them proved the smoother way in. Ultimately, we engaged a wide range of stakeholders within the organization including managers from the parent company’s Corporate Planning group, cybersecurity teams from the Digital Solutions Corporation, and employees from Toshiba’s system integration company. After a number of discussions with stakeholders at different companies, things came together and we secured a partnership for our client with Toshiba Digital Solutions.

In South Korea, one of our Intellectual Property (IP) services clients wanted to enter the market and had its sights on the country’s major conglomerates. The SK Group was an important target but it has more than 200 subsidiaries – each with its own IP and R&D teams – so the challenge was how to prioritize without missing opportunities.

We made approaches to IP teams within the various SK companies one by one and, in the end, had success engaging the SK Supex council, which shared our client’s solutions with its subsidiaries’ IP teams. This put us in touch with the right people within SK Innovation and resulted in a deal a few weeks down the line.

This centralized way of distributing knowledge, connections and solutions to group companies through SK Supex stems from the chaebol culture and is another way the corporate ‘team spirit’ manifests.

As for Korea’s Hyundai Group, its subsidiaries are more independent and their teams don’t communicate extensively with each other because their businesses are very different – or so they believe. As a result, we needed to approach and spread the word within each individually.

That said, having eventually sold our client’s services to Hyundai Motors, getting into Hyundai Steel next was easier as we had a reference within the group.

Key takeaways

There’s a lot to take in when navigating the corporate structures of keiretsu and chaebol. This might seem daunting at first due to the sheer scale of these organizations, but it’s this scale that presents massive opportunities for companies looking to do business in Asia. So, getting to know them is well-worth the effort.

Understanding how they came to be, how they’re structured and operate, how their subsidiaries and affiliates interact, what drives their decision-making, and what makes their ‘team spirit’ tick – this is how you score your big deal.

What I often do with my clients before engaging a prospect is draw a map of the target organization. We look where the end product would be produced should we succeed, identify which subsidiaries will play a role in the decision-making process, and find the best places to initiate the conversation.

If you're a UK tech company and I’ve convinced you to give East Asia’s ‘corporate cartography’ a go, I urge you to sign up to UK-APAC Tech Growth Programme for free and subsidised support – and hope to see you in Asia to help you navigate your market expansion path.

To discuss the opportunities for your business in Asia, you can contact Niklas at niklas.tawast@intralinkgroup.com.

And you can find out more and apply to join the UK-APAC Tech Growth Programme here.